“It is far better to be punished than to be treated,” is a line I can recall from some article or book that I once read, but the attribution of which is currently failing me. It speaks a truth that becomes apparent when you consider what we euphemistically call ‘civil commitment.’

We imprison people for things that they have done (or, at least, the things they were convicted of). That’s a pretty standard axiom of our criminal law. Civil commitment flips the arrangement on its head, and instead imprisoning them for what they might do.

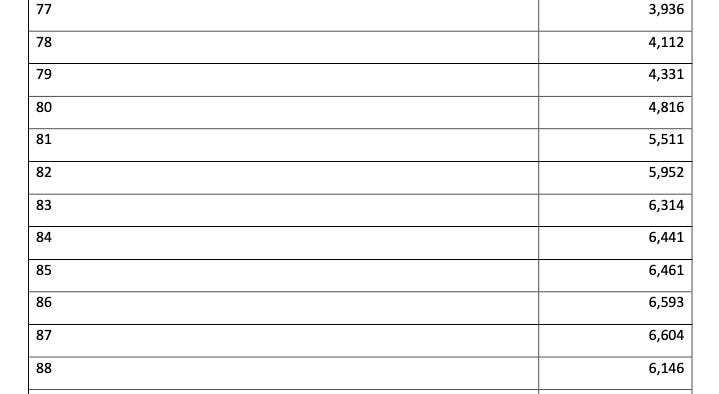

In its most muscular form, it’s applied to people who have been convicted of sex offenses. Slightly less than half the states and the federal government have the ability to, potentially indefinitely, detain people for (ostensibly) the purposes of treatment. In America, at last count, there are roughly 6,300 people detained in this manner, with Black and LGBTQ individuals 2-3X more likely to be committed than non-minority counterparts.

Last month, Virginia lawmakers introduced a bill to end the practice in the commonwealth (though it was sent to Virginia State Crime Commission and won’t be passed anytime soon). Still, it’s a notable development in an area of the law that gets little attention.

We should end civil commitment. Here’s some reasons why:

It doesn’t actually do anything.

These programs cost an enormous amount of money (see below), and for that money one would expect a return on investment — here, a reduction in sexual violence. That is, after all, the purported purpose of these indefinite detention facilities.

Recall that not every state has these programs. That sets up a sort of natural experiment — what some refer to as the idea of states as laboratories: that you can compare the results of differing state level policy to try to draw some conclusions about their effectiveness.

So, in 2013 researchers did just that looking at civil commitment schemes. The result? They discovered “that [SOCC] laws have no discernible impact on the incidence of sex crimes” using state-level data stretching back years.

Despite this, people who run these facilities will often point to low re-offense rates as evidence of their effectiveness:

The Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services said the recidivism rate for people released from the center is currently estimated at about 2%.

“If you look at our discharge numbers, despite claims, people are not held here indefinitely. They receive good treatment and it results in a reduction in recidivism and safety in the community," said Facility Director Jason Wilson.

Journalist Steven Yoder did a detailed writeup about the efforts of the state of California to bury a research study on the effectiveness of it’s own civil commitment program, after the lead researcher discovered that people who were released from commitment without treatment reoffended at extremely low rates — far lower than reoffense rates generally.

Also, if this were truly a necessary public safety mechanism, you would expect to see it in all 50 states, and anticipate that states that didn’t have them would be clamoring for them. That just hasn’t been the experience of the majority of states without these facilities, as the data would seem to support.

It’s enormously expensive.

Hot on the heels of their ineffectiveness is their cost. The states that have these facilities spend an enormous amount of money on keeping them running, and keeping the people inside imprisoned:

When the sex offender laws passed, some California mental health officials instantly grasped that the new measures were solid gold. Melvin Hunter, then director of Atascadero State Hospital, where the SVPs were sent, was elated. “Whoever came up with the term ‘sexually violent predator’ was a marketing genius.”

In their wildest dreams, California officials couldn’t have guessed just how golden. From 1996 to 2006, when the SVPs were sent to Atascadero, taxpayers coughed up $716 million to house and supposedly treat them. In 2006, the state opened Coalinga State Hospital, which cost a third of a billion dollars to build and even more than that to outfit. Over the next 13 years, the SVP tab swelled by at least another $2.1 billion. But who’s counting? Locking up sex offenders and throwing away the keys plays well with voters.

Across the country, the scene is the same. In Kansas, the cumulative 25-year tab is now $255 million to confine roughly 350 SVPs. In New York, it cost taxpayers $117 million in 2017 alone for 359 SVPs; and in Washington State, nearly $49 million in 2018 for 211 men.

At minimum, the cost per individual is roughly four times higher than incarceration, day for day (and, unlike incarceration, potentially no date when those costs stop accruing). These costs also don’t factor in, so far as I know, the litigation that occurs because of the existence of these facilities.

The money could be better spent in many other ways, including providing direct services to survivors, investing in primary prevention, or literally anything else.

It violates human rights.

In 2012, Britain blocked the extradition of an individual who was wanted on sex offense charges because American authorities could not guarantee that he would not face potentially indefinite confinement after any potential period of incarceration, referring to the possibility as a “flagrant denial” of his human rights.

In reporting I did for The Appeal on the practice, I discovered through open records requests that there were a number of states — notably Washington, California, and Florida — that had been detaining people for years, and sometimes decades, on nothing more than probable cause.

When the state suspects that someone meets the statutory criteria for confinement in one of these programs, in many states they will have a hearing to determine whether there is probable cause to continue holding them pending the outcome of their full blown “trial.” (Probable cause is, for those who don’t know, an exceedingly easy standard to meet).

There’s a lot more to be said about the conditions in many of these facilities that are often indistinguishable from jails and prisons (and sometimes, is literally a jail cell), but suffice it to say it’s a practice that gets us to some pretty uncomfortable places.

Like I said up top, we imprison people for things that they have done. Some of the people who are confined in these programs have been convicted of some pretty serious offenses, to be sure: and they were imprisoned for them. Under the U.S. Constitution, you can’t retroactively impose more punishment on an individual — except that is exactly what these programs accomplish, under the guise of offering treatment.

Most people have no idea that these facilities and programs exist — a charade of a prison within a prison. Back in an era when we had things like travel and conferences, the way I’d explain it quickly to people was to picture something like Guantanamo Bay, except we have almost two dozen of them, and for a different kind of ‘terrorist.’

Yet these facilities are nearly as impervious to judicial oversight, were born out of tragedy combined with moral panic, and appear to have a momentum all their own — such that shutting them down once they gain traction appears to be a difficult task.

If you’re interested in learning more, there is an upcoming free webinar discussing this recent report on civil commitment, details below:

(Update 2/25/21: A recording of this webinar is available at this link).