NPR Eschews Journalism in Favor of Moral Panic

Good Morning I Am Full Of Rage III: Cannonball Run

Normally, I don’t want to be writing this much but an NPR story ran today that I feel comfortable saying is journalistic malpractice. Thus, I’m compelled to say something about it. Here we are.

A piece by Cheryl Thompson ran under the headline of Sex Offender Registries Often Fail Those They Are Designed To Protect. As Stephen Hardwick — an appellate public defender in Ohio — often notes the only people that registries are designed to protect are incumbent politicians. That being the case, I would be extremely surprised indeed if the headline held up under scrutiny. And, strangely enough — it does! Just for reasons that are completely contrary to the reporting.

A bit of foregrounding: most people on sex offense registries don’t go on to commit additional offenses according to the government’s own data, and that 95.8% of all reported sex crimes that are cleared by arrest are attributable to people who aren’t or would not be on a registry. These are two unstated premises that the piece relies on for its newsworthiness, and it never bothers to mention that they’re inaccurate (thus my quip about journalistic malpractice: you’re not supposed to be making people less well informed and more afraid at the same time).

The article itself focuses mostly on how people abscond or otherwise become non-compliant with the myriad laws in various states that regulate the lives of people with past sex offense convictions who have exited the legal system:

The men are among the more than 25,000 convicted sex offenders and predators across the U.S. who have absconded, their whereabouts unknown to law enforcement or the victims — often children — whom they sexually assaulted or abused, an NPR investigation has found. Tens of thousands of others are out of compliance with sex offender registry laws.

It sounds kind of scary — especially the bit about “tens of thousands” who aren’t compliant, but that’s only if you assume that there is some kind of relationship between those laws and sexual recidivism (which is, ostensibly, the purpose of those compliance laws). What the research, of course, has generally found is that there isn’t a relationship between compliance and sexual recidivism:

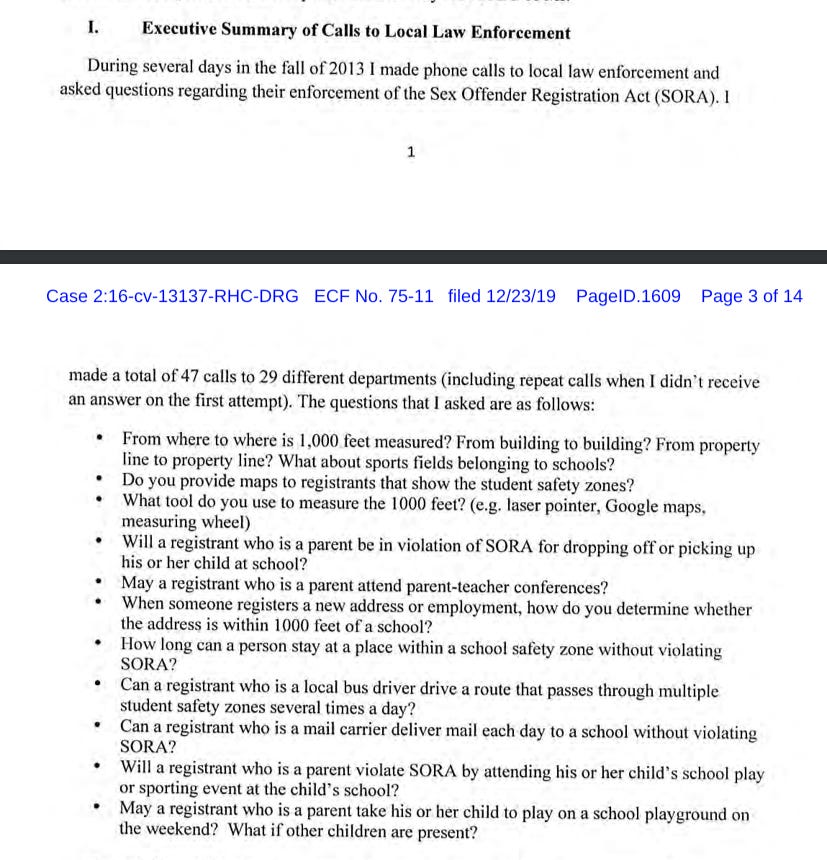

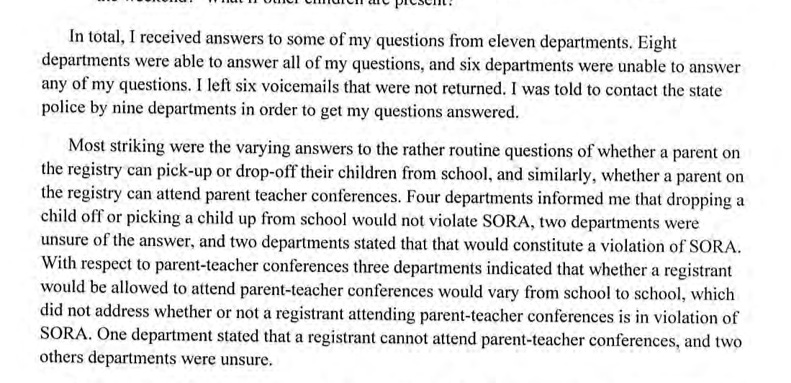

Also, compliance laws are oftentimes insanely technical that even law enforcement often can’t understand what’s required of people on the registry. If law enforcement can’t understand the laws, how are people relegated to a homeless shelter supposed to? Here’s an affidavit that was filed in a federal lawsuit in Detroit:

Oftentimes what these prosecutions boil down to is if you have ever neglected to update your license after a move, except it’s a felony offense now, except as the affidavit indicates, it’s actually much more complicated. Further, some jurisdictions reset registration time (which tend to be lengthy, like 10 or 20 years or lifetime) if someone is convicted of failure to register, meaning more opportunities to make more mistakes and commit more “crimes.” It becomes a cycle of “criminality” that is nearly inescapable.

Back to the piece:

Many state registries are rife with errors, such as wrong addresses or names of offenders who died as long as 20 years ago. Others include the names of hundreds of offenders who have failed to verify their whereabouts in more than a decade.

…

Some sex offenders commit additional sex crimes after failing to tell police their whereabouts. In Missouri, for instance, a man who pleaded guilty in 1991 to sexually abusing a 5-year-old girl was convicted in 1998 and in 2017 of sex crimes against other minors, after moving between states without registering.

It is true that many state registries have many errors in them, but again — so what? And, not for nothing, but Florida keeps dead people on its registry to keep it bloated and thus boost the federal dollars it rakes it in for maintaining it.

The assumption here is that knowing where people are, or if they are compliant, means that we’re enhancing public safety somehow. Again, research has indicated that these public registries tend to make re-offense more likely, probably by destabilizing the lives of people on the registry. Even if you know where people are, so what? Phillip Garrido kidnapped and kept Jaycee Dugard in captivity while on a registry and active parole supervision in California. There’s really no skepticism at all in the piece about that basic point, which is astonishing.

Incredibly, the reporter tracks down one of the people who the D.C. registry lists as non-compliant and interviews them. Whether or not what NPR did here is ethical — that is tracking down and hassling a 61-year old man over a 30-year-old conviction and functionally threatening him with imprisonment because his paperwork wasn’t in order — is up for debate:

NPR found Lang after checking court documents in Maryland and discovering a traffic citation from May 2019 for driving with an expired license. The court record listed an address in Northwest D.C., about 9 miles from the address he listed on D.C.'s public sex offender registry.

Authorities haven't gone after him for failing to register, despite stopping him for several traffic violations, including the 2019 incident.

..

"I've been living right here going on four years," he told NPR. "If you can find me, why the law can't find me?"

"This is ridiculous, man. I'm not hiding," he added.

At least, unlike the USA TODAY piece that ran a little while ago, it didn’t include his home address in the story. Small blessings. But the point is that Mr. Lang wasn’t “hiding,” he was just living his life, and ostensibly isn’t a threat to anyone. The piece could ask why are we harassing this man? why are we devoting public safety resources to tracking him over a crime that occurred in the early 90’s? but, of course, does not.

Also, the piece gives some context about how registries got their start:

A federal law passed in 1994 known as the Jacob Wetterling Act requires states to establish registration programs for people convicted of sex crimes or crimes against children. The law was named for a Minnesota boy abducted by a man as the 11-year-old rode his bicycle home from the store in 1989. That law also requires states to verify addresses of convicted sex offenders every year for at least 10 years.

Which is sort of ironic, because as APM’s In the Dark deftly reported, the case that spawned registries would not have been solved or prevented with one, but rather with basic, fundamental police practice that was not followed in Wetterling’s abduction and murder. In essence, the Wetterling case was an example of the government not doing its job in the first place and parlaying that negligence into asks for unprecedented power and authority: that is, the registry.

Patty, Jacob’s mother, championed these laws initially but has in recent years become a critic of the same laws that bore her son’s name. In 2019, she gave a keynote address at a symposium in St. Paul, Minnesota questioning their utility and fairness.

But the NPR starts and stops with the story of Kristen Trogler, a survivor of child sexual abuse. Her abuser, Robert Maurer, was subsequently non-compliant and also convicted of a subsequent sex offense.

Thirty years have passed since Trogler's abuse, but she relives it daily. She says she turned to drugs and alcohol as a teen.

"I was in pain," she told NPR. "I wanted to not be in this black hole that I'm still in every single day."

It is, I think, impossible not to have sympathy for Trogler — I’m also a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, and I’ve written about that elsewhere. But our criminal system, and indeed these post-conviction registration systems aren’t really designed to help survivors heal. Indeed, they’re wholly indifferent to whether or not survivor’s heal. I’m currently writing another piece that argues it’s actually in the criminal system’s interest to ensure that survivors continue to suffer, because so long as survivors continue to suffer the criminal system retains its legitimacy to inflict never-ending punishments — in other words, the trope people often use to justify these harsh punishments is that “well if survivors have to suffer forever, why shouldn’t the abuser?”

Okay, but what if they didn’t have to?

But, back to the point, what is clear is that Trogler has carried a tremendous amount of pain for a very long time, due at least in part or in whole to abuse that Maurer visited on her when she was very young. It’s just not clear how any aspect of the story is at all related to things that would have either protected her in the first place, or helped her subsequently. The piece centers Maurer’s absence from Missouri’s registry as a cause for concern, but then later observes he is serving a prison term of life without parole. His absence from the registry isn’t exactly a mystery.

Because of that disconnect, Trogler’s suffering is being used here as little more than a prop by Thompson. Were she genuinely concerned about Trogler’s suffering, it might have been interesting to examine the ways in which criminal justice processes are largely indifferent to the healing of survivors, or that these systems are undermining support structures for survivors. Indeed, as ATSA observes, vicim adovacy organizations have questioned the large expenditure of funds on sex offender management tools that may not really protect communities, while resources and services for victims are being cut.

These stories are difficult, because they are rich with pain and trauma and loss and anger and disgust. They also involve a hideously complex area of law and social science that require at least a little bit of research, that oftentimes journalists simply aren’t very interested in (as seems to be the case here).

One of the few useful quotes in the piece — which is glossed over by the reporter and buried in the middle of the piece, is from Kelly Socia, a criminology professor at the University of Massachusetts who has authored a number of research articles about this topic:

"The registry really doesn't work," Socia says. "It's a bloated, inefficient system that is incredibly expensive to maintain. I don't think it really protects anybody."

So in the end, I agree with the headline of the piece. Registries really don’t protect people they’re intended to, just for much more profound and basic reasons than the NPR article articulates.

Update: I normally wouldn’t circle back to this, except that I listened to the audio of Cheryl Thompson’s story and it is — improbably, and against all odds — even worse than the print reporting.

It opens with her accosting 61-year-old Mr. Lang on a basketball court where she tells the listener that he is a regular since being released from prison for rape, but that he isn’t properly registered with DC authorities. She does not mention in the audio that his crime was almost 30 years ago, and that he was released from prison almost 20 years ago (which to her credit, she does at least include in the print reporting). She then proceeds to tell his neighbors about what he did three decades ago (to be fair, I have no idea if Thompson did that, or simply referred to him as a convicted rapist who was non-compliant and asked for their response).

In both the print reporting and the audio, she heavily implies that Lang and the other people she writes about are intentionally evading these requirements — referring to them as “absconders,” but at least notes in the audio that Lang gave authorities a different address than the one that was on the registry. If Lang were intentionally evading these requirements, as opposed to simple neglect or forgetfulness, wouldn’t he make sure to provide police with the address he is supposed to be at?

Thompson also, inexplicably, discloses that Lang suffers from AIDS, despite that not being relevant in any way to her ostensible lede. It is needless, thoughtless, empty cruelty.

The one subject who didn’t make the print reporting, but does appear in the audio is a veteran living in a VA long-term care facility in Illinois who was convicted of sex abuse more than three decades ago. He, too, was not properly registered so Thompson reached out to police who then issued an arrest warrant for the presumably ailing man.

To be clear, I am not defending what either he or Lang did decades ago. But what this reporting indicates, is that so long as the subjects of your story have done something bad in the past that they were held accountable for — no matter how long ago it was — you’re free to ignore essentially any ethical considerations when reporting on them. Is it ethical that you’re seeking to imprison terminally ill senior citizens in the middle of a pandemic for the equivalent of not having their paperwork in order? Is it ethical to disclose the HIV/AIDS status of a subject of your story, when that has no relevance at all to your lede? Maybe it is, but I certainly don’t think so. Either way, I’m confident that these were not questions that neither Thompson nor her editors at NPR even bothered to consider.

UPDATE: NPR Released a Part 2 to this story, and it’s also bad!

Stealth edit: Wanted to also add Joshua Vaughn’s work on this particular issue, which squares with the wider criminological research.

NPR should be NPW - Now Purely Woke. Their reporting on issue after issue is slanted, agenda driven. Facts are distorted to fit the story to be made.

An issue that I care about and know a lot about is immigration. NPW is completely pro-illegal. They are also pro-work-visa. When they do stories on either issue, they have biased panels. They don't listen to both sides. The reporters on these issues are often illegals themselves, and have an agenda to justify their own existence. Very shoddy stuff.

As you state, the lie that sex offenders are dangerous predators needing to be tracked and monitored should be obvious to any thinking person. The facts just don't support the hype.