My father was on his back in the emergency room bed, doing what I can best describe as an impression of a bug trying to turn over, his arms and legs flailing, connected to tubes and sensors, some kind of macabre marionette. It was two weeks before his eightieth, and two and a half years after he had a stent placed in an artery. A tiny piece of wire mesh that saved his life. That time, he had walked himself into the hospital in the midst of a heart attack, improbably and tragically, at the the same time my then-sister-in-law collapsed to the ground alongside her husband, vacationing in the Caribbean. Her heart gave out at 23. Within the span of an hour, he lived, she died. Very little about who lives and who dies makes sense to me. She was a good person. Her death made this world we share a little colder.

On this night, my dad had a fever of 104. Septic shock, I was informed. The stats, I learned later, did not favor him, but I could intuit that from the energy in the room, my mother by his side. Cursing my inability to do much more than to hold his hand, I told him he was too stubborn to die, careful not to betray what I hoped my voice might project with the raging and terror going on inside me, as if I might simply convince him of that fact and he might survive through sheer thick-headedness. I’m good in a crisis, but then, so is he. I guess I come by it naturally then. Saving my tears and snot and prayers for the midnight walk around the nearby park when I couldn’t sleep, the same park he used to take me jogging at as a kid—almost always against my will—when I needed a “mood altering experience.” And God did I need one. Jogging certainly does alter your mood, first negatively, then positively if you go long enough.

Having a close relationship with your parents is a blessing. But there is a catch. The flip side of being fortunate to have parents that that have always showed up for you, is that it’s going to hurt very badly when it’s time. Whether that’s time to say goodbye, or whether that’s time for the child to become the parent. I am not ready for this, but then, who is? That day comes for us all.

And, they have always been there for me.

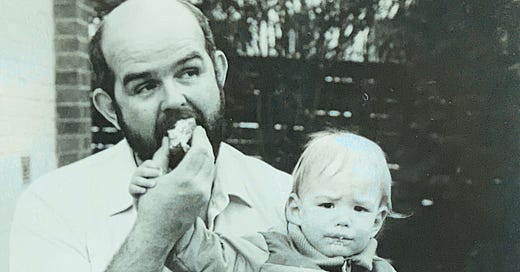

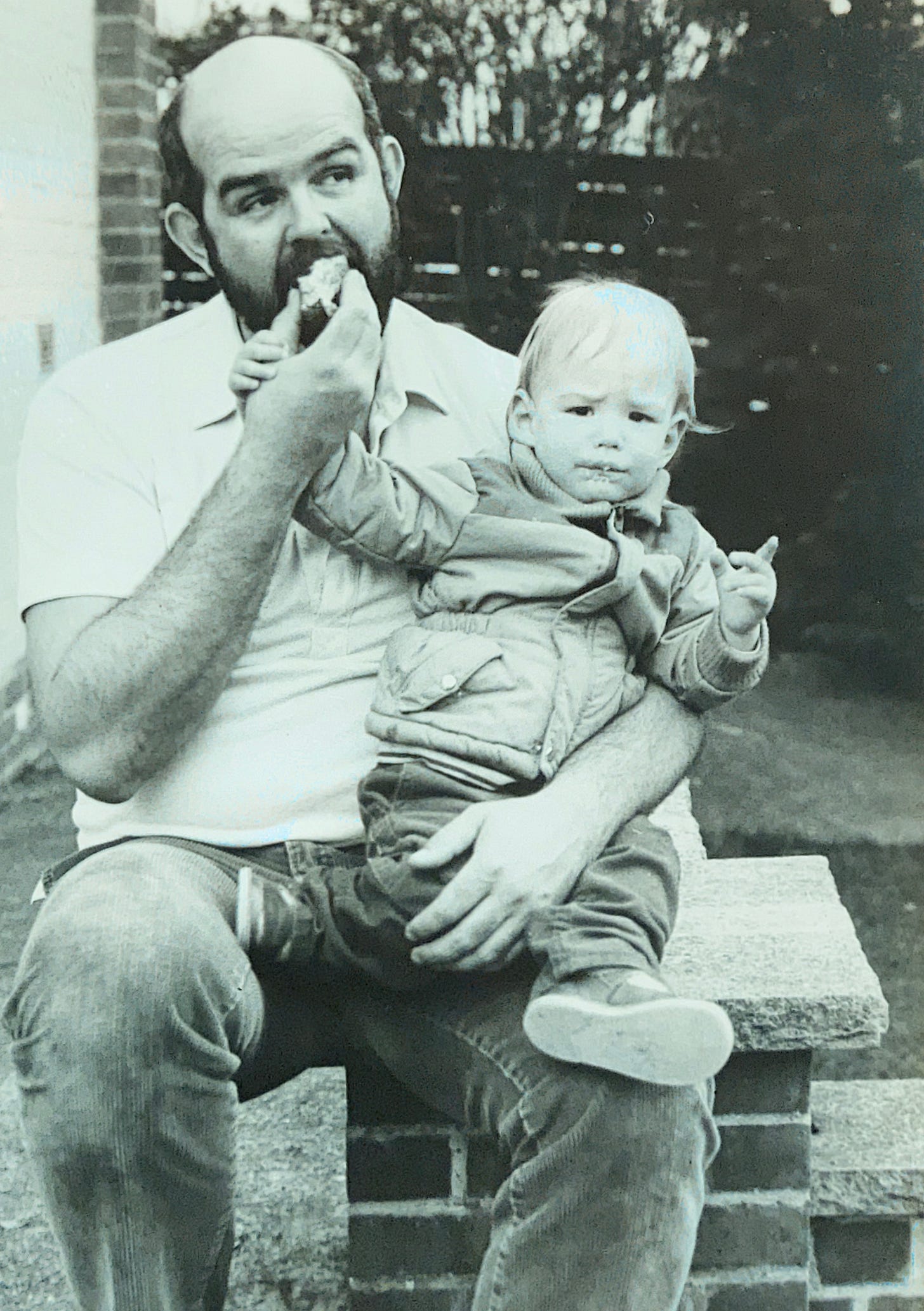

My father’s been many things, worn many hats. His first memories were of military and tanks rolling down a dusty street in Iran the 50’s, fall of the Shah. Sometime later, half a world away, a student at MIT fighting off two muggers on a dingy street in Boston in the 70’s. One of them had a knife, tried to stab him. Then, a corporate bulldog with a corner office in San Francisco, a hard-charging negotiator. Met my mom there. Scientist. Consultant. Then a high school science teacher who often butted heads with the administrators—unsurprisingly to me. Sometime along the way, also a dad, mine. Now, crossing guard. He does a job where he gets thanked, and that has very little moral ambiguity. It is hard to argue with stopping kids from getting run over. He has a police department hat and vest. I humorously asked if they gave him a gun, too. I guess not all cops are bad.

Some of his students told him he was the best teacher they ever had. I can see it. Once, he taught me how to change the drive belts on my mother’s beaten up Sonata in the parking lot of their townhome. A stranger wandered up to us, and we chatted. I remember his name was Rico, and he looked imposing: well-built, tattoos. He was friendly, and asked if we were father and son, which is obvious to anyone that looks at us—we look almost exactly the same. Moreso now that I am balder, older. He told me I was lucky, and headed off on his way, while my dad and I worked to unstick a bolt. He was right in ways that are hard to express, and that at the time, Rico’s wisdom—I suspect, hard earned but freely given—was mostly over my head. I just hadn’t lived enough yet.

Kids. They’re always testing you, my father’s fellow high school teacher remarked as my dad was hurriedly packing up. My dad told him that he had needed to go home, that I had been arrested for a crime. He didn't know what it was, only that it was serious.

Not this one, my father replied. That wasn’t entirely true, however. The number of times he dragged me out jogging attests to that. Certainly not today. It was probably about that time that I was being loaded into the police transport van, perhaps 50 feet or so from where I had an hour earlier suspected I might land after going over the railing of my 17th floor balcony.

Oh. I hope it all works out, then.

The detectives were kind, though they would not let me have a cigarette, assuring me I could have one at the jail. I was young enough to believe that. The jail staff, too. The booking officer who signaled to me that I should lie about whether I was a suicide risk — something I would not understand until after law school that he offered me a kindness. The pretrial officer who commanded me not to discuss my charges, though I didn’t need a Juris Doctor to understand the bloody sort of business she left unsaid. I suspect they could clock I was enveloped in terror, and they were correct. Even still, I felt a strange sense of relief after the confession. Life is full of paradoxes: the freest I had ever felt was in a pair of handcuffs. One thing I was certain of though, was that my parents would disown me. My life, obviously, was over. There was, sadly, no immediately obvious way to kill myself in the jail. I didn’t even get a room, just a cot in the hallway. Hard to hang yourself from that.

My bond was $15,000, full cash. Normally they reduced it to 10%, but not for me. Nature of the crime. The following morning, the ATM wasn’t working. At the bank, there were several people waiting inside their cars for the clock to strike 8am to make their financial transactions, headlights and windshield wipers going in the October rain, engines idling softly, likely wondering who the strange man guarding the front door of the bank was, getting soaked. My father had wagered that if he was physically closer to the door than anyone else when the staff unlocked it, the question of whether he would be their first customer would be a rhetorical one, soggy or not. It was a good plan.

I had spent the night dodging inquiries, and doing my best to seem unbothered. I am sure my best was not very good. My dress shoes, arranged neatly outside of my holding cell at the police station that afternoon, nearly betrayed my feeble attempts at subterfuge amongst my countrymen in booking, them disbelieving that I was taken in for questioning for possessing weed. The charge was possession, so I was only half lying. After lights out, I was mostly left alone to lay on a cot in the hallway of one of the pods of the detention center. That day, in grad school, I had learned cognitive behavioral techniques we could use for clients to reduce anxiety. I had learned them just in time.

Do you want to go home? The officer had asked me with what I detected was a soft edge of some kind of sympathy, after she had barked my name, summoning me from my cot to the control center where she stood, an array of panels and switches.

Yes. Because, what the hell else do you say.

My bond was posted. I was processed out. The ride up the elevator, the walk down the hallway, through the double doors, and there they were. My parents embraced me in the lobby of the detention center. I told them I was sorry. I was dying for a cigarette. My dad was still damp from the rain. They told me they loved me.

The arraignment. It was a word I had heard on Law & Order, but now, I had my own. You are informed of the charges against you, conditions of your release, and your next court date. My father had gotten me a lawyer, too. One he had hired before to help him with a DUI some years ago. He was nice, smart, sympathetic. I trusted him. We were originally told by police the charges were misdemeanors, but a few months prior, the legislature had upgraded them to felonies. My lawyer broke the news. My mother sobbed.

The arraignment took place in what seemed to me to be a cavernous room. Portraits on the walls, wood paneling, a wooden bar separating the front third of the room where there was the judge sitting at an elevated desk, staff, court security. The rear two-thirds, wooden pews full of all kinds of people. I took a seat as instructed, waiting for my turn.

Eventually, they called my name. Just, with a Commonwealth versus in front of it.

I took my spot at the podium in the front of the room, past the wooden bar, next to my lawyer. You are charged with three counts of possession of material portraying a sexual performance by a minor, the judge announced to the room. The charges weren’t even the worst part. The worst part was that it was true. I felt the electricity change. The usual murmur from the crowd during the other cases stopped. I felt heat behind me, some kind of fire back there. When the judge and my lawyer finished, I turned and looked at the faces, looking back at me. I was assailed with emotions I would come to know so very well — shame, stigma, judgment. They probably wished I was dead. So did I. I was transfixed.

Somehow, I had to get out of this room, but going back the way I came seemed impossible. It was impassable now, the walkway washed out, but the lawyer nudged me. I had to move. I shoved my hands into my pockets and fixed my gaze on the patterned floor, my sole mission: escape. I thought maybe the window. I couldn’t look up to see the way out for fear of meeting anyone’s gaze, but I knew the layout of the room. It was simple. Two long aisles on either side of the bar, doors at the back. I would have to go by memory. Faster, faster, go, go, go. I believed I might die if I didn’t reach the door in time. I know what it feels like to be on Mars, the distance between myself and any other human being. I was there.

Maybe I was halfway out now, half expecting someone to tackle me. Maybe wanting it. I was struck, indeed, but instead by something like a lightning bolt. Get your hands out of your pockets, and keep your head up. My father’s voice. Low, like a whisper, but somehow also loud, like an explosion inside my head. Stern. He had maneuvered through the other bodies in the room and found his place next to mine, shoulder to shoulder with the pariah. I did as he said, almost on reflex, like when the doctors hit your knee with the little rubber triangle hammer thing. He did love me, and here was the proof, a rescue mission to Mars.

It isn’t that we always got along. He hit me once when I was a kid. I hit him back once, too, when I was older. My parents blamed themselves for a while for my arrest, until I convinced them it wasn’t their fault. I made my choices, but I was too scared and ashamed to get help. I did test them in many ways. I have a better grasp on the depth of what Rico meant.

The next couple decades happened. My parents listened to God knows how many moot arguments when I was on trial team and moot court in law school. My dad once played the role of Dusty Stockard, a veterinarian in a mock dog-fighting case, and witness for the defense. Owing to his experience as a real-world expert witness, he proved exceedingly skilled at escaping the traps my fellow law students tried to set for him on cross. My “client” was acquitted. They helped me move houses, they helped me move on from heartbreak. Helped me find a place to live when I was homeless. Helped me heal through many things I believed would kill me, and nearly did. Celebrated with me. Hugged me when I screwed up. Never let me forget that they loved me, not even in my darkest moments. Tell me they are proud of me. I’ve told them many times I’m sorry for the things I’ve cost them. They tell me they would do it all again. That it was never a question, getting drenched in the morning rain for the sole purpose of making certain there would be no waiting in line, and all the other things, too.

I’ve been wrong about many things, including my certainty of being disowned. More recently, however, I was right about my dad being too stubborn to die. His fever broke with the antibiotics. The doctors discovered he had afib, and treated that as well. He’s feeling better than he has in quite some time. I cannot express my gratitude for the nurses and doctors that treated him, and the technology that made it possible. What a time to be alive. I thanked even nurses and doctors who had nothing to do with my dad, on the way out of the hospital, for the work they do, someone else’s dad they save, or mom, child, brother, sister. They tended to react with surprise — why is this weirdo thanking me?

Someone on Twitter once said that if you have parents that love you and support you, it’s like a superpower. Yes. It is.

My story has been so very public in many ways. Initially, I took that to be a terrible burden. Sometimes, it isn’t easy. Mostly, I see it as a gift. I have gotten many emails and letters and phone calls over the years from parents whose children are in trouble. I have worked with clients who have parents who love them very much. Sometimes, a parent who gets their child a lawyer, like mine did for me. We are here, I believe, to be of use to one another. I can be useful.

Love them. Anything over the last two decades I have done that might be called an accomplishment is ultimately owed to that act. It doesn’t solve everything. It is painfully evident that sometimes, that love is not enough. The world is still the world. But it solves a lot, as giving your kid a superpower might. You’d be surprised what that can overcome. I know I’ve been.

My dad called me recently to go for a walk through one of the parks he would take me jogging through many years ago. He moves slower now, uses a cane. His jogging days are over. We got to talk about the news, the birds, politics, my work, his childhood. He still defeats me easily at Jeopardy every time it’s on. I do not know how he knows so many things. He and my mother are both insistent on coming to my oral arguments at the Sixth Circuit in Cincinnati next week, despite his cane, despite her walker. They promised not to cheer. Dad purchased some fossils and minerals he was very excited to show off to my mother and I, his giddiness about rocks figuring him closer to 8 than 80, aping a schoolboy at show and tell.

I know that day is coming.

But not today.

I hope that I’ve made you proud. Or if not, that I will.

What a lovely tribute! I’m close to weeping with some common emotional impacts in our lives. So well said! Thank you!